- Home

- Leah Kaminsky

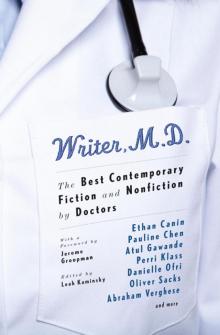

Writer, M.D.

Writer, M.D. Read online

LEAH KAMINSKY

Writer, M.D.

Leah Kaminsky is an award-winning writer and a practicing family physician. She is the author of four books, including Stitching Things Together, a collection of poetry. She has studied writing at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, New York University, and Vermont College of Fine Arts, and is currently at work on her first novel. She lives in Melbourne, Australia.

A VINTAGE BOOKS ORIGINAL, JANUARY 2012

Copyright © 2012 by Leah Kaminsky

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Originally published, in different form, in Australia as The Pen and the Stethoscope by Scribe Publications Pty Ltd., Melbourne.

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Owing to limitations of space, permission to reprint previously published material may be found on this page–this page.

The Cataloging-in-Publication Data for Writer, M.D. is available at the Library of Congress.

eISBN: 978-0-307-94687-4

www.vintagebooks.com

Cover design by Mark Abrams

v3.1

For Yohanan, Alon, Ella, and Maia Loeffler

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Foreword

Introduction

nonfiction

Bedside Manners Abraham Verghese

Index Case Perri Klass

Resurrectionist Pauline W. Chen

Intensive Care Danielle Ofri

Falling Down Sandeep Jauhar

Beauty Gabriel Weston

Do Not Go Gentle Irvin Yalom

The Lost Mariner Oliver Sacks

The Learning Curve Atul Gawande

The Infernal Chorus Robert Jay Lifton

fiction

We Are Nighttime Travelers Ethan Canin

Dog 1, Dog 2 Nick Earls

The Duty to Die Cheaply Peter Goldsworthy

Finding Joshua Jacinta Halloran

Tahirih Leah Kaminsky

Communion John Murray

About the Authors

Acknowledgments

Medicine is my lawful wife and literature my mistress; when I get tired of one, I spend the night with the other.

—Anton Chekhov

Foreword

A physician works at the border between science and the soul. Schooled in physiology and pharmacology, the molecular workings of genes and proteins, the biochemistry of health and disease, a doctor brings to care a diverse body of expert knowledge. That knowledge is rapidly expanding with the use of sophisticated technologies such as genomics that map mutations in our DNA, and MRI scans that reveal millimeter abnormalities in our inner organs. This wealth of information has changed the nature of diagnosis and treatment, bringing many maladies under the bright light of science, illuminating their genesis, and providing a rational basis for their remedy.

But what has not changed over the millennia is the human soul. The role of the physician as healer has not been fundamentally altered by his burgeoning knowledge. Greater knowledge does not necessarily translate into greater wisdom. Wisdom requires melding information with judgment and values. The wise doctor probes not only the organs of his patient but also his feelings and emotions, his fears and his hopes, his regrets and his goals. And to accomplish that most important task of applying wisdom, the physician also needs to take his own emotional temperature, to realize how his own beliefs and biases may be brought to bear in his efforts to secure a better future for his patient.

This remarkable collection melds science and the soul, logic with feeling, knowledge with wisdom. The voices that the reader hears are among the most prominent in the constellation of physician-writers. What makes these writers so compelling is not only the fluidity of their prose and the intensity of their focus, not only their literary and narrative skills, but also their remarkable degree of self-awareness. A physician is trained in medical school and residency to hide his feelings and filter his thoughts. This training is required in order to effectively deliver care in an environment that is often chaotic and unnerving. The doctor needs to present himself to the patient as a safe harbor of stability in the midst of the tempest of illness. But when that doctor has moved from the clinic to the page, the mask drops, and we see the turmoil and tribulations in his heart and mind. The humanity of both patient and physician is what makes the stories that follow so rich and so fulfilling.

Jerome Groopman

Introduction

When I first became a medical student, many years ago, I developed a condition I call Tunnel Vision of the Soul. It is a crippling ailment in which you see only things that are straight in front of you. You focus on the sickness and don’t see the sick person. Your peripheral vision is blurred, so that you don’t notice your surroundings, with all their inherent colors, nuances, and possibilities, unless you deliberately turn your head to look. The onset can be insidious, the symptoms barely perceptible at first.

As I was spending lunchtimes in the anatomy museum, surrounded by dissections under glass, it never occurred to me that what lay exposed was the pelvis of someone’s mother, or the foot of somebody’s brother. I munched on chicken sandwiches, busily memorizing mnemonics: Swiftly Lower Tilley’s Pants To Try Coitus There, for the bones of the wrist; Grandpa Shagging Grandma’s Love Child, for the top layers of the skin.

After six years as a medical student, practicing rectal examinations on old men who had become paralyzed following a stroke, performing bone marrow biopsies on dying little old ladies, and shoving needles into the spines of crying babies, I emerged almost totally desensitized to human pain and suffering. My fortnightly salary checks were based on the fact that other people fell ill, or died. And as a cocky young intern, proudly wearing my long white coat while strolling through the wards of a large teaching hospital, I felt impermeable.

The cure for my tunnel vision came gradually. I started reading literature, which coaxed me to return to writing—something I hadn’t done since high school. With my trembling pen, I began to heal my own wounds and try to make some sort of sense of what I had experienced as a young doctor and as a human being.

Since that time, my medicine has always fed and informed my writing. More important, my writing has hopefully made me a better doctor. Becoming a writer has opened my eyes, so that I am able to see my patients as human beings, each one with his or her very own story to tell. And nowadays, I hope that I am able to listen to their hearts—with both my stethoscope and my pen poised.

Writer, M.D. is a collection of stories—fiction and nonfiction—that aims to look behind the doctor’s mask. What goes on inside the mind of the human being who deals with enormous existential issues and traumatic situations on a daily basis? It is through writing that many doctors have plumbed the depths and richness of their experience and, in turn, used this to explore their patients’ inner lives.

These stories canvass emotional experiences acutely felt by doctors—an awareness of our mortality, of how humanity interplays with medicine, of the weight of responsibility carried by the profession. The fiction pieces, in particular, often use the point of view of the patient to examine a range of issues, including grief, trauma, illness, and aging.

The public is hungry to see behind the veneer of the medical professional, as evidenced by the burgeoning number of TV shows such as ER and Grey’s Anatomy. This book delves beyond sensationalism, taking a critical look at doctors’ close observations of, and reflections upon, their working lives.

Physician-writers have a long tradition. Apollo manage

d to have a dual career as the Greek god of both poetry and medicine. Copernicus, Maimonides, Bulgakov, and Chekhov were all physicians who purloined their patients’ narratives. In this anthology, I hope the reader will be afforded a glimpse of the world through the eyes of some of our best contemporary doctor-writers. Every patient has a story to tell, if only you take the time to listen.

Leah Kaminsky

nonfiction

Bedside Manners

ABRAHAM VERGHESE

When it was time to hang pictures in our new house in San Antonio, my wife asked me to buy a stud finder. As a husband, I demurred; as an internist, I flat-out refused. We internists make it our business to divine the stutters and stumbles of lungs, hearts, brains, adrenals, guts, gonads—hence the term “internal medicine.” Once upon a time, doctors examined patients not with CAT scans or MRIs but with their senses. “Surely,” I said, “skills that can find pus behind the chest wall can find a stud behind drywall.”

Under her skeptical eye, I dragged my fingertips along the wallpaper. I flattened my palm and tapped on the back of my left middle finger using the tip of my right middle finger. My hands drummed over the pressed gypsum, sounding it, discovering the spots where the resonance became muffled, abbreviated—thud rather than thoom. In the medical world, this is known as percussion, a technique that physicians have employed for centuries to sound the body’s depths. Using it, I had found the upright wooden timbers that even in the best circles of society are called studs. My brother-in-law, who fought in Korea, who wears ten-gallon hats, and who is fond of me but feels that most medical professionals are in it for the luxury cars, golf, exotic vacations, and early retirement, was impressed. As we hammered the nails in and hung the pictures, he said, “I didn’t think a doctor could do that anymore.”

My wife thinks of me as a Luddite. She believes that if a gadget has found its way onto a catalog page, and if its price is many multiples of a bar of soap, it must be useful. But that evening the pendulum swung in my favor. It was one of those man-puts-machines-to-pasture moments where the sheeplike drift of consumer society toward another “must have” is momentarily halted. Please, I beg you, say no to pet dishes on legs that enable Fido to drink in an “anatomically correct” fashion, say no to battery-operated fridge air purifiers, and say no to stud finders. I fell asleep that night thinking about an instructional pamphlet that I would put in every homeowner’s Welcome Wagon basket, alongside the coupons, refrigerator magnets, and recipes for orange-peel-flavored scones: “Find the Hidden Stud in Your New Texas Home.”

The sad thing is that a homeowner armed with such a pamphlet and with one other critical ingredient—faith—can soon become more skilled at percussion than the average physician. It is fast becoming a lost art. In the past twenty-five years, I have taught hundreds of medical students the four classic steps in the physical examination: inspect, palpate, percuss, and auscultate. Their eyes sparkle. This is the way they imagined themselves: semioticians at the bedside, reading the signs to find the varmint in the patient’s body. Alas, a shock awaits the students when they finally arrive on the wards in the third year of medical school, their pockets laden with reflex hammers, tuning forks, ophthalmoscopes, otoscopes, penlights, and stethoscopes, only to discover that the ebb and flow of the modern hospital centers on MRIs, CAT scans, echocardiograms, angiograms, and myriad lab tests. Often, interns and residents have so little faith in bedside diagnostic skills that, as one student told me, “a man with a missing finger must get an X-ray before anyone will believe he has only four.” As for neat pocket tools, only a few diehards still carry them. The stethoscope alone peeks out of the doctor’s pocket as a hollow symbol of the profession. (I prefer seeing it in the pocket to seeing it draped over the neck like the beads and gris-gris of Wodaabe tribesmen of the Sahara, a vulgar display meant to signal that the wearer is a sound marriage prospect and has, if not cows and land, then the prospect of luxury cars, golf, exotic vacations, and early retirement.)

When I travel as a visiting professor to teaching hospitals, I have the distinct feeling that the patient in America is becoming invisible. She is unseen and unheard. She is “presented” to me by the intern and resident team in a conference room far away from where she lies. Her illness has been translated into binary signals stored in the computer. When I ask a question about her, the intern’s head instinctively turns to the computer screen, like a pitcher checking first base. I gently insist we go to the bedside, but that is often a place where the team is no longer at ease. I realize what has happened: the patient in the bed is merely an icon for the real patient, who exists in the computer. How strange this is! When one knows how to look, the patient’s body is an illuminated manuscript. Indeed, in an elderly patient with a double-digit “problem list” that scrolls off the screen, only at the bedside does one understand which problem is most important. As my brother-in-law would put it, “You have to kick the tires.”

I am no economist, but even a landlubber on a sinking ship is entitled to make observations about the rent in the hull that is about to alter his fate: the present crisis in American health care is only secondarily a fiscal one; the real crisis is that the “art” of bedside diagnosis at which a previous generation excelled has died with the next. Personal-injury lawyers allow us the wonderful excuse that we order batteries of tests because we are practicing “defensive” medicine. The truth is that, even without the threat of malpractice, we would still need just as many CAT scans and echocardiograms as we do now. We know no other way. Take away our stud finders and we can’t hang a picture. We are like owners of playerless pianos asked to entertain during a blackout: our fingers and ears may be intact, but we can no longer play or percuss.

It was an innkeeper’s son, Josef Leopold Auenbrugger, who discovered percussion. I have dreamed this scene so often that I am convinced it must have happened. Imagine Vienna in the eighteenth century:

The inn is bustling. Young Josef and his father carry empty wine jugs down to the cellar. Auenbrugger père hums as he descends, the sound enlarging in the cool cavern, where three large casks of wine sit like three portly giants. Since the casks are not transparent, the question is always how much wine remains inside each one.

Auenbrugger père raps with his knuckles on the side of each cask. At the top he generates a hollow sound, a profundo, like a bass drum. As his knuckles come down the side, there is a point where the sound changes. The sustained echo—the thoom—is stifled, and the new sound is dull and flat, as if the old sound were decapitated. Young Josef, just like his father, “sees” through the cask, where the reflective, liquid surface ripples at his touch.

In Auenbrugger’s time, physicians focused largely on symptoms, and had no great need to touch the patient (which some would argue is where we are now). Knowing what ailed you made little difference because, as far as treatment went, you could only be cupped, purged, scarified, or bled. Bleeding was to that era what antibiotics are to ours: abundant and overused. At the barber-surgeon’s establishment, you held on to a pole as he sliced you and collected your blood in a basin. While there, you could also get a tooth pulled, an abscess drained, and finish up with a shave and a haircut. The barber-surgeon was nothing if not versatile. At the end of the day, the barbers washed long strips of bandage and hung them outside to dry. Medical students are often surprised when I tell them that the familiar red-and-white barber’s pole has its origins in bloodletting, with the stripes representing the bloody bandages and the ball on the top of the pole representing the basin. If you had a chance to live, these treatments might nevertheless do you in; if you were destined to die, they mercifully hastened the end.

When Auenbrugger became a physician, he started thumping and tapping on his patients, and painstakingly cataloging the sounds of health and disease they produced. The book he wrote about this practice, Inventum novum, published in 1761, had the impact on medicine that X-rays would have 150 years later. For the first time, a doctor could “see” beneath the intact

skin into the innards of the body. Percussion allowed (and still allows) a physician to get evidence of a dilated heart, an enlarged liver, fluid around the lung, fluid in the belly, a perforated stomach ulcer, and many other conditions. I think of present-day ultrasound as the child of percussion, the ultrasound transducer generating a sound wave that bounces off the tissues and comes back to a sensor.

Like any new method, percussion had its overenthusiastic practitioners. The famous Pierre Piorry percussed while sitting on a high stool next to the patient’s bed, and then used colored crayons to outline the organs. Known as the “medical Paganini,” Piorry claimed each organ had its own note and the body held a musical scale. An apocryphal story has Piorry going to see the king and, on being told that the king was out, proceeding to percuss the chamber door and declare that the king was in.

I attended medical school on two continents. My first clinical professor in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, was a spiritual descendant of Auenbrugger’s named Charles Leithead. He taught us how to place our fingers on the wrists of patients with rheumatic heart-valve disease and recognize the slapping, “water hammer” pulse of a leaky aortic valve or the “plateau pulse” (pulsus parvus et tardus) of a narrowed aortic valve. He marched us to the heart, taking the blood pressure along the way, studying the sinuous waveforms of the neck veins, which mirrored the happenings in the heart’s upper chamber. He carefully inspected the patient’s chest and felt for the thrust of the heart between the fifth and sixth ribs on the left, though in an enlarged heart, the impulse could wander down and out to the armpit. At this point in an exam, he had us pause and try to put the clues together. His teaching was: “Before you pull out your stethoscope, you should know what you are going to hear.” It was heady, marvelous stuff. When I finally heard the soft, rumbling, low-pitched, mid-diastolic murmur of mitral valve narrowing that is caught only with the bell of the stethoscope lightly applied, I was ecstatic. I heard it because I knew it would be there.

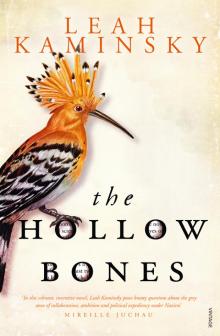

The Hollow Bones

The Hollow Bones Writer, M.D.

Writer, M.D.