- Home

- Leah Kaminsky

Writer, M.D. Page 2

Writer, M.D. Read online

Page 2

Displaced from Africa by civil strife, I went to Madras, in South India, to finish my studies. My teacher was the legendary K. V. Thiruvengadam, known to all as KVT. KVT is the Ravi Shankar of percussion. He enjoined us to “percuss to feel and not to hear.” The vibration we received in the pleximeter finger laid flat against the chest was, he said, more important than the sound. You can recognize KVT’s progeny from our near-silent percussion; if I percuss audibly, it is only to teach, or to demonstrate, say, to a skeptical brother-in-law or spouse.

For sleuths of the caliber of Leithead or KVT, a diagnosis could be lurking in something as simple as a facial expression. Not the dull and coarse facies of a sluggish thyroid or the masklike expression of Parkinson’s disease, which are evident to laypeople, but the risus sardonicus (sardonical smile) of tetanus or the facies latrodectismica (a grimacing, flushed, jaw-clenching, puffy-eyed expression) of a patient affected by the toxin from a black widow spider, or the madonna-like facies and transverse smile of a type of muscular dystrophy.

My final exam at the medical school in Madras included a rigorous clinical test with real patients carefully selected for signs and symptoms of a disease. In America, final-year medical students face no such clinical test. Even for specialists in internal medicine, testing with real patients and live examiners was done away with in the mid-seventies, after it was deemed too subjective. Recently, the powers that be put in place the national Clinical Skills Assessment Exam for final-year American medical students, for which the student has to cough up more than a thousand dollars and travel to one of a couple of centers in the country. In my opinion, and the opinion of many academics I talk to, this exam tests everything but clinical skills. It tests the student’s ability to make eye contact, to interact with a person acting the role of a patient, to follow the appropriate leads in his fictional story. Does it test whether the student can detect an enlarged liver? Or hear the diastolic sound of heart failure? To get a driver’s license or a pilot’s license, it is axiomatic that an examiner must watch you drive or fly to confirm you have the skill. Not so in medicine.

I recognize that I am an incurable romantic. I teach bedside skills because I hear the ghosts of Auenbrugger; of the celebrated physician Sir William Osler, who took us out of the classroom a century ago; and of the old horse-and-buggy doctors in South Texas who could divine their patients’ maladies by touch, smell, sight, and sound. I hear them say, “Thou shalt not break the chain.”

For the past few years in San Antonio, I have spent Wednesday afternoons on “professor’s rounds” with six or seven third-year medical students, seeing patients they have worked up. Each week, when I round with a new group, I ask them not to tell me or the other students what the patient’s diagnosis is, so that we can see how much the body alone might reveal. The students love these sessions. They often say that this is what they envisioned medicine would be about: time spent in the hallowed space around the patient’s bed, time spent with the patient, probing the body for clues. I preach that it is a skill they should cultivate, not to replace technology but to allow them to use technology judiciously and to ask better questions of the tests.

At a recent Wednesday-afternoon session, our patient, an elderly veteran, was thrilled by the attention from the flock of students, particularly their percussing of his chest. “My doctor used to do that when I was a boy,” he said with a smile. “He sure knew what he was doing.”

Index Case

PERRI KLASS

Because of my extensive training—four years of medical school, three years of pediatric residency, a two-year fellowship in pediatric infectious diseases—and because of my years of experience in practice, I had no trouble at all diagnosing my illness. I knew what was wrong with me, and I knew the technical term for it: I had the pediatric crud. It was winter, and I was seeing sick kids all day long, and now, after a couple of days of congestion and rhinorrhea, a bad cough was developing. It happens every winter, like clockwork.

Now here comes my big confession. I am ashamed to admit that on day one of my bad cough, I started treating myself with antibiotics. Yes, of course, I knew that in all probability I had a viral upper respiratory infection (URI), and I could probably even have named the most likely viruses. And yes, of course, I knew that antibiotics were completely useless in the setting of a viral URI, and I knew that the overuse of antibiotics is a terrible problem in our society, and that the demands of patients with viral illnesses and URIs to be treated with antibiotics need to be met with careful education and explanations—certainly not with unnecessary prescriptions. I knew all that, really I did.

On the other hand, I also knew that in winters past, when my annual pediatric crud dragged into its third or fourth week, I usually ended up taking antibiotics. I would wait until my symptoms qualified to be considered bronchitis, or until a colleague listened to my lungs and heard some crackles; but, in the end, my annual illness would always lead to antibiotics. So since this cough seemed to have gotten so bad so quickly, I reasoned, why not just take the antibiotics right away and see if I could shorten the course? Well, maybe “reasoned” isn’t quite the right verb. Let’s just say that, more than a little shamefacedly, I treated myself with a five-day course of azithromycin.

It didn’t help at all. My cough got worse and worse. I didn’t feel too sick otherwise, but I was carrying around a jar of maximum-strength over-the-counter cough medicine, dosing myself whenever I had to see patients, teach, or do anything else that called for conversation. I viewed it as my right and proper punishment for taking unnecessary antibiotics. It never occurred to me to stop seeing patients, of course; nor did it occur to any of my coworkers, I would guess, that perhaps I shouldn’t be working. I wasn’t really sick, I just had the crud, and we’re all wedded to that die-with-your-boots-on ethos whereby you keep on working unless you are sicker than your sickest patients. One day, when I was responsible for hospital rounds, I did ask a colleague whether she thought it might be better to have someone else run over to the hospital and see a couple of newborns—I have this pretty dramatic cough, I said, and I feel a little guilty about coughing in the newborn nursery. My colleague, supremely unimpressed, and much too tight for time herself to fit in an unexpected hospital stop, sensibly suggested that I try a gown, a mask, and gloves.

So, well swathed, I rounded on the babies, and then I went on to work the evening session at the health center, seeing patients. I took the maximum-strength cough medicine and washed my hands scrupulously, and whenever I felt a coughing fit coming on in the presence of a patient, I would make some excuse to leave the room and go cough my head off in the doctors’ work area. Then, the colleague who had suggested the gown and mask heard me coughing that very night and remarked that I sounded paroxysmal.

Now, “paroxysmal” is one of those coded medical words. It’s like saying a baby seems a little “lethargic,” rather than simply tired and clingy and cranky. You say it one way, you mean the baby has a little bug; you say it the other way, you mean do a lumbar puncture. So when she said “paroxysmal,” I thought, for the very first time, of pertussis (whooping cough). And once I had started thinking about it, I couldn’t get it out of my mind—after all, I had my cough to remind me. So I went to my internist, who thought my lungs sounded fine and that my cough probably just represented a lingering viral illness—and these coughs, she warned me, can last for some time—and that pertussis was highly unlikely. But to allay my anxieties, she sent off a titer (I was more than two weeks into the cough by this point, so it was too late for a culture). And then I went back to seeing patients, and the laboratory misplaced the sample (by filing it under my first name instead of my last, it turned out), and I had to call a friend in Infection Control, who got someone at the lab to take another look, and eventually the sample was found—and guess what? I had pertussis.

I had suddenly become a public health emergency. A pediatrician, seeing children all day, rounding on newborns, the mother of three children at three di

fferent schools, the close colleague of who-knows-how-many doctors and nurses and clerical staff. I was phoned or paged by someone from Public Health every day, sometimes several times a day. I sat at my desk making a list of every friend or acquaintance with whom I had been in close contact during my infectious period.

I felt deeply, deeply ashamed. Calling these people, one after another, I felt alternately like Typhoid Mary and the person at the end of the STD partner-notification line. I had exposed them, contaminated them, put them at risk. I urged everyone to take prophylactic antibiotics, to call the doctor immediately if a cough developed. Most of all, though, I felt ashamed before my colleagues and my patients at the health center. I couldn’t stand to look at the letter that was going out to the families I had seen during my period of maximal infectiousness: “Your child may have been exposed to a staff member who has pertussis.” I did not want to be the doctor who saw any of those families when they came in to get their antibiotics or, if they were coughing, their nasal swabs and their antibiotics. I did not want any of them to know that I was the staff member with pertussis. And to make matters worse, I was still coughing—now not infectious but still coughing pretty dramatically, just in case the local public health emergency had slipped anyone’s mind for even a minute.

Some of my anxieties were relatively well grounded in reality. Pertussis, after all, is most dangerous to infants, who account for almost all the hospitalizations and the deaths associated with the disease. And the surveillance data show a steady increase in the rate of disease among infants in the United States between 1980 and 1999—an increase that may be attributable in part to increased transmission from adults.1 And here I was, one of those adults. We do know that much pertussis disease in adolescents and adults may present as nonspecific or persistent cough, and may therefore go unrecognized.2 We do not know why the rate of disease in adults should be on the increase, if in fact it is. The confluence of various factors may be to blame: the waning immunity of the vaccinated adolescent and adult population, for instance, and the decreased likelihood that immunity will be boosted by exposure to natural disease.

I was an adult, vaccinated as a child, presumably with waning immunity, which had probably been boosted by exposure to some natural disease during my childhood, forty years ago, and perhaps by the occasional occupational exposure (I can remember at least two occasions during my residency when prophylaxis was prescribed, though I have to confess that, back in those days, when two weeks of erythromycin were required, my compliance was dubious and I probably did not finish either course). Maybe my own waning vaccine-induced immunity finally intersected with a sufficiently infectious exposure—but epidemiologic speculation feels different when you yourself are the index case. What I kept picturing were sick babies—individual tiny bodies wracked with coughing fits. There were all the infants I had examined in the clinic, there were the babies in the nursery … there was even a friend who had shared a cab with me who had a newborn grandchild, and I imagined the chain of risk and exposure stretching far enough to threaten that baby as well.

Of course, I had seen pertussis. I saw a very dramatic case during my residency, in an infant who had deliberately not been vaccinated (“crunchy granola parents,” we residents whispered to one another), who was brought into the emergency room looking terrific, but his parents had tape-recorded his coughing spells, telling us they had never heard anything like this. And indeed the spells were terrifying: you listened to the tape, and you could swear the baby was dying of strangulation before your very ears. And at the end of each spell came that terrifying unearthly whoop, as if the baby were possessed by some evil-intentioned spirit of respiratory compromise. Every resident and medical student in the hospital was brought to that baby’s room during his hospitalization, and the word was passed: once you hear a real whoop, you’ll never forget it (an audio clip is available at www.nejm.org). Well, I had never forgotten it, but adults, by and large, don’t whoop, so it had never occurred to me that I might have the same disease as that baby. Some pediatric infectious diseases specialist; some diagnostic whiz kid!

I’m not sure now exactly why I was so ashamed. Presumably, after all, I had contracted pertussis in the line of duty—pediatric infections are an occupational risk and, for all our careful hand washing, if you see sick kids all day long, sometimes some enterprising microorganism makes the jump, through direct contact, through fomite, or through respiratory droplet. It is a professional responsibility, and even a professional point of pride, not to run from the sick but to move toward them and touch them. But there was something about the idea that, instead of helping, I might have gone from day to day and from exam room to exam room doing harm that left me deeply embarrassed. In addition, I was embarrassed that, despite all that training, the word “pertussis” never crossed my mind until someone else listened to my cough with interest and characterized it for me.

There was only one really bright element in those bleak few days, as I huddled over my list of exposed friends, calling them up one after another with the bad news, as I went slinking through the health center imagining resentful looks from nurses and doctors and patients alike: at least I had taken antibiotics, and taken them early. The public health nurse who was assigned to my messy case kept saying it to me on the phone: “Thank God you took those pills!” Because I had started taking azithromycin (which, in Massachusetts, is now a recommended treatment for pertussis) on day one of my cough, I was considered to be noninfectious by day five, so instead of contacting and prophylactically treating about two weeks’ worth of patients, we ended up with a relatively short list of children who might have been exposed—and the consolation that even when I saw many of those children, I had been at least partially treated, which might have reduced the risk of transmission. Those babies in the newborn nursery, for example, were not considered to be at risk. And I found myself saying it to my friends, when I called to notify them: “Now, I did take antibiotics right away, but since we spent some time together before I was fully treated, I just wanted to let you know …” And as time went on and we failed to uncover any secondary cases that could be traced to me, I kept reminding everyone about that early antibiotic treatment, as if it let me cling to some shreds of doctorly dignity: I had done the right thing, I had used my special knowledge, I had protected those I could protect. In other words, I consoled myself for my irrational sense of shame about having possibly exposed patients to infection with an irrational sense of self-satisfaction about having taken antibiotics for no good reason.

Pertussis may be on the increase in this country, but in many ways it still seems like a disease that does not quite belong to our era. When I had to call people and announce, “I have whooping cough,” I felt like a medical curiosity, or the punch line of someone’s ironic anecdote: the pediatrician with the rare, vaccine-preventable disease. When the public health officials were calling me, I felt like some other kind of epidemiologic specimen: patient zero, the walking disease-control headache. And through the whole experience, every so often, all my various emotions would disappear into a true and impressive paroxysm of coughing, coughing, and more coughing, as the microbiology and the respiratory pathology took over and left me doubled over, momentarily speechless, and gasping for breath.

Notes

1. M. Tanaka, C. R. Vitek, F. B. Pascual, K. M. Bisgard, J. E. Tate, T. V. Murphy, “Trends in Pertussis Among Infants in the United States, 1980–1999,” Journal of the American Medical Association 290, no. 22 (2003): 2968–2975.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Pertussis—United States, 1997–2000,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 51 (2002): 73–76 (available online at www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/wk/mm5104.pdf).

Resurrectionist

PAULINE W. CHEN

My very first patient had been dead for over a year before I laid hands on her.

It was the mid-1980s, and I had at last made the transition from premedical to full-fledged medical student. That la

te summer from the window of my dormitory room, I could see the vastness of Lake Michigan dotted with sailboats and the grunting, glistening runners loping along its Chicago shores. Despite this placid view, I rarely looked out my window. I was far too preoccupied with what lay ahead: my classmates and I were about to begin the dissection of a human cadaver.

Prior to that September, the only time I had seen a dead person was at the funeral of my Agong, my maternal grandfather. Agong had grown up on a farm in the backwaters of Taiwan at the turn of the last century. He barely finished high school, but by the time he was middle-aged, Agong owned a jewelry store in one of Taipei’s most fashionable districts and had raised five college-educated children. While he grew up speaking Taiwanese, Agong had taught himself Mandarin Chinese and Japanese, languages and dialects as different as German, English, and French.

Agong loved my mother, his firstborn child, and lavished her with that gift of nearly blind parental adoration. As her firstborn child, I was in a special position to receive some of those rays of love. Unfortunately though, with my American upbringing I understood Taiwanese but spoke only “Chinglish,” a pidgin amalgamation of English and Mandarin Chinese. Moreover, Agong and I had been separated by half a world until he moved permanently to the United States when I was in high school. So while I loved my grandfather, our relationship always remained rather formal.

Agong died in the fall of my sophomore year in college. One weekend, my parents mentioned to me on the phone that he was doing worse and might possibly “not make it.” A week later they called again to tell me that he had passed away.

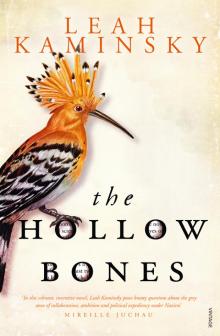

The Hollow Bones

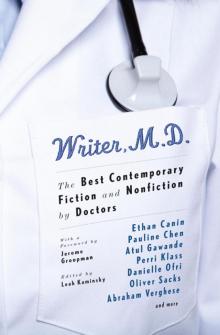

The Hollow Bones Writer, M.D.

Writer, M.D.